This is your world in which we grow,

and we will grow to hate you.

Solo exhibition

18 February - 19 March 2010

Brodie/Stevenson, Johannesburg

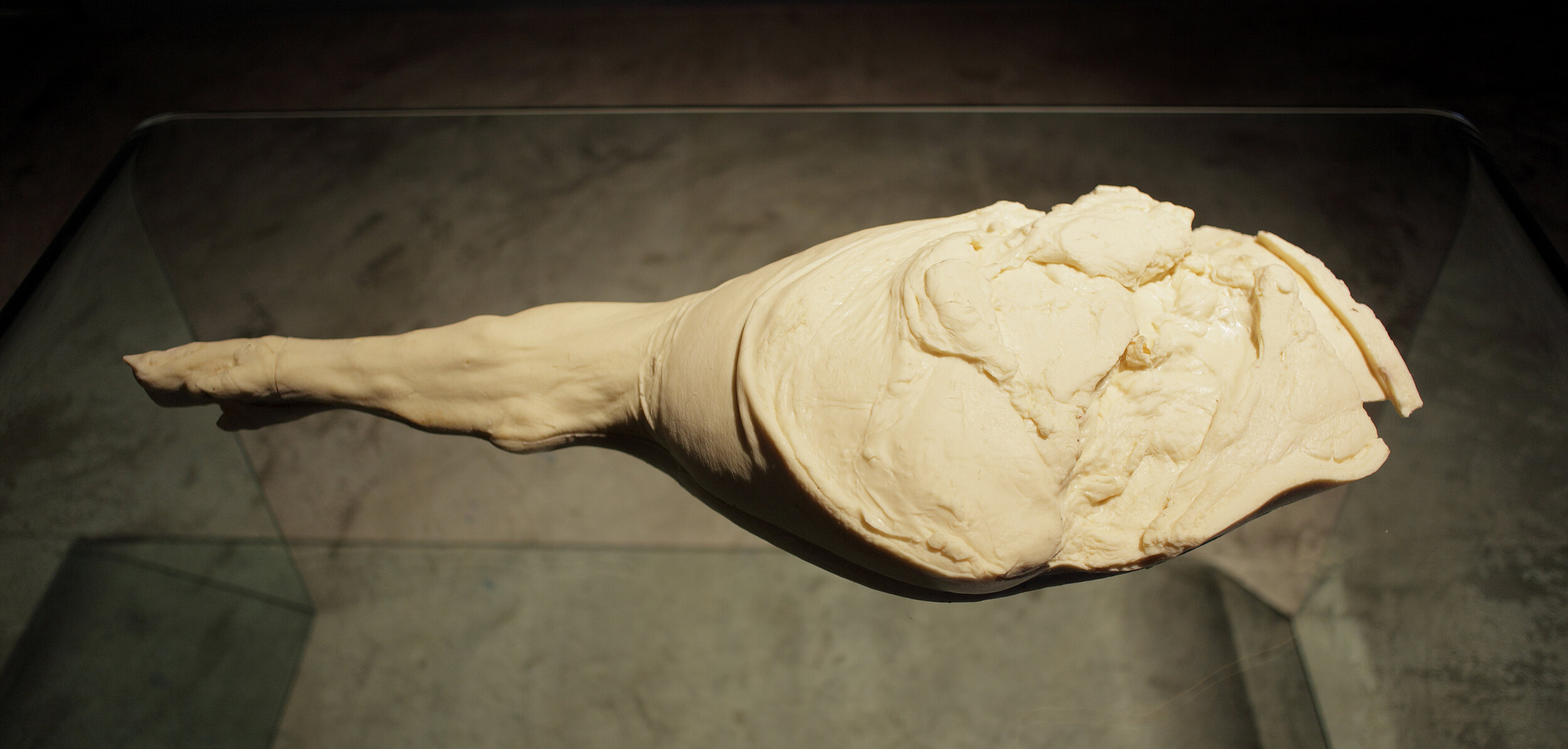

Above –

African National Congress

White milk chocolate, armour-plated glass

700 x 280 x 100 mm

2010

Private collection

Within the context of sub-Saharan Africa, my concern is to investigate the ways in which the newfound and existing exploitation of hydrocarbons is in many ways an extension of the colonial-era legacy of ‘mercantile capitalism’. Coupled with a contemporary resource-grab scenario that pitches oil producing nations within the region as one of the new energy frontiers, with numerous developed and developing economies – internationally – competing for the secure exploitation and export of these natural resources. This context as a whole is understood and defined within the broader scenario of ‘peak oil supply’ in the contemporary global market place.

The focus of this exhibition is on several key areas of interest; principally Angola, Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea and South Africa. Various new works manifest hybrid, fictional products and totems from these contexts pitched within and borne from research into the highly complicated and obdurate machinations of political life within these four countries – historically, within the present-day and coupled with conjecture as to possible future scenarios. The overall optic is one of a critical optimism, coupled with legacy issues around the notion of the resource curse. Works such as Dutch Disease look to the effect of oil extraction has had historically in countries like Nigeria and Saudi Arabia, coupled with conjecture within emerging oil exporting countries like Angola and Equatorial Guinea to name but a few. An economic theory coined in 1982 by economists W. Max Corden and J. Peter – Dutch Disease, or the Curse of Plenty, describes and unpacks the relationship between the exploitation of natural resources and the attendant devastation of domestic manufacturing, followed by systematic loss of employment and general societal decay. In South Africa, this concept is all too evident. The machinations and complicity of the minerals-energy complex with Black Economic Empowerment and the ruling elite within post-Apartheid South Africa, have manifest an adverse effect on local manufacturing – and definitively falls within this resource curse matrix. The sculptural work titled African National Congress, directly addresses this – South Africa is rich in natural resources, and while our economy is very diversified, our socio-economic context does suffer – to varying degrees – from a similar curse of plenty evident in countries like Gabon, Venezuela, Saudi Arabia and Nigeria. South Africa’s manufacturing sector has steadily declined over the past 15 years, resulting in a loss of jobs coupled with a lack of new job creation to offset these losses. Newly cast into a globalised economy, we remain uncompetitive within this sector, a status further aggravated by a radical influx of cheap goods from the Far East without trade restrictions or tariff barriers. South Africa’s mass population is kept in check – to various degrees – by the ruling elite principally through social grants. Lacking the capacity for concrete entrepreneurship and development and consequently unable to generate employment for a substantial percentage of the populous, our government is forced to pay the economically disenfranchised to simply exist. And to suppress dissent. It is an institutional, social bribe that maintains the status quo.

Yet, these processes we, as South Africans, are currently engaged in as a resource-rich, post-colonial society are, to a large extent, predated on the African continent by some 30 to 40 years. Works such as Mercantile Capitalism interrogate the characteristics of political elites in African nation-states post-independence – their power dynamics and the quality of leadership. Of particular focus is Gabon and Nigeria, while the title refers to the larger absence of any broad-based industrial revolution on the continent, where the economies and social structures established under colonial rule are, to large extent, still in place today. These systems have been strategically retained by political elites post-independence to meet the needs of their own convoluted, expensive and Baroque political processes, coupled with substantial personal consumption. This corruption is often defined and decried from a Western, democratic optic – whereas the realities within these African countries often dictate perverse processes and behaviours to maintain power – often in fractious, violent states and within political systems that cannot be trusted and effectively managed even by their own leaders. Yet, there is no bourgeoisie to drive entrepreneurship. Exports and GDP, in a great many instances, are overly reliant on the export of unrefined or unprocessed natural resources to the developed world. Thus, creating a steady and reliable income stream to these often Baroque ruling elites. The number of oil producing countries in Sub-Saharan Africa is on the rise (there are currently 17) and has seen the growing influence of China, India and Malaysia increasing the competition for access to these resources away from the traditional control of European (France, Britain, Holland, Norway) and North American commercial oil interests.

Oil has, from its very inception been an international commodity, and over the past 150 years it has systemically grown to be supplied globally. It has allowed us as a species to use tomorrow’s energy, to create 24 hours of sunlight, to grow astronomically in our capacity to produce food, technology, cities, wars and even more humans. That oil is traded and transported internationally is by no means a new phenomenon – what is precedent is its global demand. Until recently it was principally the first world that used any meaningful volume of oil – the current global Peak Oil scenario is the result of a steady climb in demand from the developing world, coupled with a systematic depletion of domestic oil production within these first world countries, and the growing cannibalisation of domestic production by oil producing nations themselves over the past 30 years. The term Peak Oil describes the point of maximum global crude oil extraction, immediately followed by a terminal decline in production. In visual terms the concept can be understood in terms of Hubbert’s Curve – where the graph steadily climbs, then reaching a peak, is followed by an identical trajectory down again. In real terms this means we will soon be producing the same amount of oil as we did in 1980 – yet with an attendant population explosion in the second half of the previous century and the continued rise in demand in the developing world as well as demand globally – the rate of production will not keep pace with demand. The issue is not that oil will run out within our lifetimes – it is rather that there won’t be enough to supply our insatiable global demand for it. In turn, creating an environment of increasingly expensive oil. The repercussions of this environment were seen last year where the Brent Crude barrel price reached a staggering $147.50 – and almost single-handily caused the collapse of the global economy. The often cited claim that the collapse of the residential housing market in America caused repercussions that soon swept through multiple markets, and in term a collapse of the whole system, falls well short of the mark. Expensive oil was responsible – we use it for everything. The price increase of the magnitude we saw last year makes every single aspect of our lives more expensive. This structurally undermines our globalised economy, which is exclusively based on the uninterrupted supply of cheap oil. Without any other viable energy alternatives, this cycle of rising crude oil prices followed by systemic economic collapse will continue unabated in our Peak Oil age. We live in a world where the future, most certainly, belongs to those of us willing to get our hands very dirty.